To understand the reasons for deforestation in Guatemala you need to know about how agriculture played a role in it. Deforestation in Central America is deeply

intertwined with the historical patterns of land ownership and the inability of

such systems to accommodate rural population growth. As capitalists understood the profits of export crops in Central America, commercial growth gained momentum. Foreign commericial produce distributers worked with gorvernment officials to obtain land where they could produce and harvest foods for world-wide distribution. Land confiscation from small farmers who provided for the local economy and owned land in prime farming areas

was the primary means of increasing production. This furthered land scarcity among

vast numbers of the peasant farmers who still needed to make a living to resort to deforestation of hills to survive in less optimum farmlands which in turn caused

soil erosion by clearing hillsides for their crops. In addition to the

exhaustion of marginal lands as a result of demographic pressures;

commercialization contributed directly to deforestation and soil erosion

through rapid conversions to cotton, sugar, and beef production.Some of the less vulnerable farmers were able to convert their harvest into what they thought would be a faster/higher yeild in their land through raising cattle, cotton, or sugar which depleted the soils even further. This model for export expansion increases

the total amount of land under export production without establishing

sustainable and efficient land tenure.

To understand the reasons for deforestation in Guatemala you need to know about how agriculture played a role in it. Deforestation in Central America is deeply

intertwined with the historical patterns of land ownership and the inability of

such systems to accommodate rural population growth. As capitalists understood the profits of export crops in Central America, commercial growth gained momentum. Foreign commericial produce distributers worked with gorvernment officials to obtain land where they could produce and harvest foods for world-wide distribution. Land confiscation from small farmers who provided for the local economy and owned land in prime farming areas

was the primary means of increasing production. This furthered land scarcity among

vast numbers of the peasant farmers who still needed to make a living to resort to deforestation of hills to survive in less optimum farmlands which in turn caused

soil erosion by clearing hillsides for their crops. In addition to the

exhaustion of marginal lands as a result of demographic pressures;

commercialization contributed directly to deforestation and soil erosion

through rapid conversions to cotton, sugar, and beef production.Some of the less vulnerable farmers were able to convert their harvest into what they thought would be a faster/higher yeild in their land through raising cattle, cotton, or sugar which depleted the soils even further. This model for export expansion increases

the total amount of land under export production without establishing

sustainable and efficient land tenure.

Influences on Land

Tenure

Here is where it starts getting technical. When examining the issues of

land tenure in Guatemala, both prior to and after the agricultural reforms of the mid-twentieth century,

it is necessary to also consider the socio-political and economic systems which

are associated with, if not responsible for such inequalities in land

distribution. Political control of the Ladino landed elite over the rural

peasantry was largely exerted through political repression and suppression of

land reform movements ultimately resulting in a civil war.Technological control was also exerted, as it

was the government and landed elite who have both promoted and subsidized

technology and research to their political and economic advantage. Agricultural expansion in Guatemala

has consistently sought to promote export production over domestic food

production; diminishing autonomy and access to land without providing either

the intended sustainable economic development or the food security needed by

large portions of the rural population.

Colonial Agricultural Models: Cacao and Indigo

The current system of land tenure in Guatemala is modeled after systems initiated in colonial agriculture and have developed as a result of the continued expropriation of communal

lands for production of export commodities. Starting with the confiscation of existing cacao orchards by the

Spaniards and their utilization of indigenous populations to fill labor quotas

through their organization into centralized villages; the search for wealth at

the expense and exhaustion of natural resources and indigenous populations

became the general model.Little focus was given to the foodstuffs needed to feed the indigenous

peasants causing both famine and labor shortages, which when compounded with declining

orchard health, spurred the need for an alternative export crop. Indigo followed cacao, but failed because of

an inadequate labor supply, as well as inaccessibility of markets. The expansion of the hacienda

system during the eighteenth century signaled the shift in conflict from the

supply of labor to the supply of land as colonists ventured out from the cities

seeking the most productive lands, leaving only the more marginal lands of the

highlands and costal lowlands for the indigenous populations.

Coffee

By 1810, fifty years after the Central Americagained its independence

from the crown, the desire for a lucrative export crop

was met by the emergence of coffee. The

lands best suited for coffee production were those at moderate elevations, the

majority of which were inhabited by subsistence peasants. Confiscation of communal lands was enacted as

land titling reforms, and reallocation of such lands was based upon the

expansion of coffee production, which required substantial capital unavailable

to peasant farmers. Yet again, export

potential was limited largely by labor; which was consequently assured through

legalized forced labor such as mandamientos and debt peonage.

Foreign Banana

Companies

Though coffee production continued

successfully, another export crop was established in Central America

by the end of the Nineteenth Century. Large tracts of coastal lowlands were ceded to foreign banana companies

in exchange for infrastructure developments, such as regional railroad lines,

which were necessary for both banana production and distribution as well as for

growing industrialization efforts.At the time these grants were made they presented no real conflict with land

tenure patterns, but the vastness of such landholdings ultimately came in

conflict with the land needs of growing rural populations. Additionally, the extreme power that these

companies held in Central American politics and economies had direct effects

upon the opportunities facing rural indigenous populations. The United Fruit Company was Guatemalas

largest land holder, though 85% of their holdings were not under

production.During the massive land

reforms of the 1950s under President Arbenz, 2.7

million acres of uncultivated lands was expropriated from multi-nationals and

Ladino elite in an attempt to return that land to food production through

distribution to over 100, 000 families (Healy, 2003).Because of the international power of The United

Fruit Company and the allegations of communistic leanings of the Arbenz government, the U.S.

launched a destabilizing campaign which resulted in the resignation of

President Arbenz and the return of the majority of

the expropriated land (Barraclough

and Scott, 1988).

Boom/ Bust cycles of

Post World War II Expansion

Central American economies were damaged by

World War II, and eventual economic recovery was characterized by a push for

rapid economic development through a diversification and expansion of exports

(Brockett, 1998). Cotton, sugarcane, and

beef production grew rapidly as a result of government promotion. The Pacific

lowlands were previously considered uninhabitable and unmanageable from a

growing perspective because of lack of roads and pesticide technology, but

became extensively utilized during this period of expansion. The lands needed for increased production of

cotton, sugarcane, and beef during the postwar period were in addition to those

needed for steadily growing production of traditional export crops such as coffee,

nearly 40% of the forests in 1961were destroyed by 1978 (Brockett, 1998). Consequently, the periods economic successes

must be viewed in the context of furthered inequalities in access to land,

self-sufficiency, and autonomy within the rural populations.

Cotton and

Sugarcane Expansion

Central American economies were damaged by

World War II, and eventual economic recovery was characterized by a push for

rapid economic development through a diversification and expansion of exports

(Brockett, 1998). Cotton, sugarcane, and

beef production grew rapidly as a result of government promotion. The Pacific

lowlands were previously considered uninhabitable and unmanageable from a

growing perspective because of lack of roads and pesticide technology, but

became extensively utilized during this period of expansion. The lands needed for increased production of

cotton, sugarcane, and beef during the postwar period were in addition to those

needed for steadily growing production of traditional export crops such as coffee,

nearly 40% of the forests in 1961were destroyed by 1978 (Brockett, 1998). Consequently, the periods economic successes

must be viewed in the context of furthered inequalities in access to land,

self-sufficiency, and autonomy within the rural populations.

Cotton and

Sugarcane Expansion

By 1964 the largest 3.7% of

farms in the Pacific lowlands occupied 80.3 % of the land, and within fourteen

years the amount of land under cotton increased ten-fold (de Janvry, 1981).

Cotton was in the tradition of the boom/ bust cycle of production and

exploitation, particularly because of its annual life cycle, which allowed for

fluctuations of annual acreage based upon varying demand. Consequently, cotton producers increasingly

used indiscriminate amounts of pesticides without focusing on sustainable

production practices, and often

converted to sugarcane production when cotton prices bottomed out.

Beef and Deforestation

Beef and Deforestation

The Seventies

and Eighties presented yet another potential export commodity, and rapid

conversion to beef production was also largely promoted by governmental and

external loans.It is estimated that

during this period over half of the loans made to Central America promoted the production of beef for export markets. The beef industry played a significant role

in further deforestation through its continued search for grazing lands. Uncleared land was

often rented out to subsistence farmers at minimal prices and then converted to

beef production once the land was cleared.

Political Control of the Landed Elite

Political control has been

characteristic of all periods of Ladino rule in Guatemala,

but this control became increasingly violent in the second half of the 20th

century. From the Fifties on, the

majority of Guatemalan presidents had a military background and gained support

of the army through relegating a large degree of power to it. Proletariat leanings of many of the peasant

movements hastened the almost complete repression of social organizations,

trade unions, and political parties.The

calls for land reform were largely restricted and consequently began to take on

illegal forms. Counterinsurgency

campaigns of the early Eighties aimed at depopulating areas of guerilla control

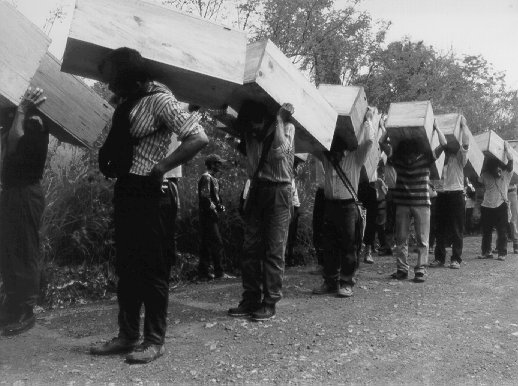

and support. Over 440 whole villages

were destroyed, with more than 100,000 civilians either dead or missing (Healy,

2003).Such destruction not only reduced

rural populations,displacing them

through massive relocation programs, but also affected further deforestation

and environmental damage through an attempt to minimize physical groundcover

available to the guerillas ( Healy, 2003).

Technological

Control of the Landed Elite

Technological control of the

landed elite was exerted through policies determining technological and

agricultural research and subsidization (de Janvry and Dethier, 1985).

The rural landless lacked the political power to demand innovations

which would be applicable to their needs.

Consequently policies promoted expansion of large scale export

production in search of economic growth and international markets. Farm research by organizations such as NARS

was based almost exclusively on the fertile farmlands of the lowlands, and was

therefore inappropriate to the vast numbers of subsistence farmers (Bebbington et al, 1993).

In addition to

the self-serving interests of Ladino farmers were the self-serving interests of

foreign investors who played a key role in determining which technologies and crop productions

would be subsidized ( Tucker, 2000 ). Reliance upon foreign aid for internal development proved highly unreliable in developing

sustainable agricultural systems because such support could be withdrawn quickly,

as was seen in Guatemala in the late 80s when spending on public research and

extension declined by 48 per cent and 60 per cent respectively between 1989 and 1991 (Bebbington,

1993).Similarly, export promotion aid

from the U.S.

totaled 82 million dollars for the entire period of 1954 through 1982, and in

1983 alone this number rose to 32 million dollars drastically shifting the Guatemalas

agricultural economy with out

sustained commitment to continue such trends.

Current

Deforestation continues at a rate of 2.05% annually (World Resource Institute,

2003). Despite economic expansion, access

to international markets has failed to increase the independence, autonomy

,and food supply for

the majority of rural populations.In

1950 landless families composed only 15% of those involved in agriculture,

where as in 1980 that number was estimated to have risen to25%.

Bimodal Agricultural Systems

By 1980

Guatemala had the most skewed distribution of land in Latin America (Healy, ),

a framework which has come to be referred to as bi-modal or dualistic in reference

to the vastly different production and consumption patterns characterizing the two separate components of the

economy. By 1983 88% of the total number

of farms occupied a mere 14% of the land, and were considered sub-family farm

units unable to provide adequate food

supplies for the families who farmed them (Brockett, 1998). Another significant component of the minifundio and latifundio bimodal

system is the role of foreign aid as food imports,which discouraged domestic production

of food crops through cheap food prices.

U.S. food aid to Guatemala totaled 93 million for the entire period between 1954 and 1984, where as in

1985 alone it totaled 20 million. Lacking the capital needed for the higher

technological inputs of competitive export production, and no longer able to

sell staple crops at competitive prices many subsistence farmers were obligated

to seek off-farm incomes in the export market.

Additionally, technological advancements on large landholdings were not

managed solely in an attempt to maximize profit, market share. Because landholdings were viewed as

low-return and low-risk investments, largely valued as maintaining economic and

social security, they were often not managed with land efficient production

practices (de Janvry, 1981).

This inverse relationship between farm size

and efficiency of production is increased when an analysis of the quality and

environmental marginality of subsistence and commercially productive lands is

included.

Agriculture in 1998 accounted for 23 percent

of the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), and food products represented 61 percent of

Guatemalas exports in 1998. Coffee has been Guatemalas most important

export for more than a century, and despite considerable diversification, in

1999 the country produced 204,300 metric tons. Sugar has been rising in

importance, and Guatemala harvested 18 million metric tons of sugarcane in 1999.

Bananas remain important and are grown in the tropical lowlands, mainly by

foreign corporationsincluding Chiquita (formerly United Fruit and United

Brands), Fyffes, Dole, and Del Monte. But as world demand for bananas has

declined, as soil has been depleted, and as other crops have been developed,

banana production has become a much smaller percentage of total exports than

formerly.

Since the 1970s Guatemala has been the

leading exporter of cardamom, a spice popular in Arab countries. Falling prices

for this crop, however, have diminished its importance, and in 1995 it accounted

for only 2 percent of Guatemalan exports. In 1999 fresh fruits , oilseeds , and

vegetables were significant crops. Guatemala no longer exports cotton, which

until recently was a major export. Cotton output dropped dramatically from

165,698 metric tons in 1985 to a mere 7,500 metric tons in 1999, because of both

production problems and wide competition from other regions and synthetic

fibers.

Export agriculture has absorbed so much of

Guatemalas limited arable land that food production has suffered. Corn

remains the principal crop for domestic consumption, but significant amounts of

rice, beans, sorghum, potatoes, soybeans, and other fruits and vegetables, as

well as livestock, are also raised.

Guatemalas large forests, estimated at 9.5

million acres in 1995, have been declining at an average rate of 2 percent

annually, as trees are cut for firewood and construction timber. Some valuable

stands of mahogany and cedar remain. In 1998 timber production reached 478 cubic

feet.

The commercial shrimp and fish industries

have grown in the 1990s, with the yearly catch increasing from 2,782 metric tons

in 1985 to 11,303 metric tons in 1997. Domestic seafood and freshwater consumption is small and growing smaller with overfishing areas that may have had a high yield five years ago.

Considering that populations growth is

inherent in the future of developing countries, land demographics is an unavoidable

issue and vital to both the economic and environmental health which will face

future generations. The largest threat

to Guatemalas environment is continued deforestation as well as the soil

erosion associated with the exhaustion of marginal lands. Capitalistic perusal of export crops by the

landed elite, starting in the Colonial Period and continuing through the Twentieth

Century, has failed to provide a sustainable model of development for the

country at large. The world trade also affects the local farming in that selling prices fluctuate drasitcally enough to make or break a farmer once they have invested all their money into one type of crop. The efficiency of

agricultural production practices are contextual and must be considered in

terms of the demographic, political, and cultural effects on the country at

large. Consequently, environmental

solutions must take all components of rural economies into consideration

when attempting to affect comprehensive and sustainable solutions. Solutions may be one of educating locals as to what is unique to the natural environment here and assisting them in marketing in a world market for those products.

World Resource Institute. 2003. Recent data on

environmental and agricultural conditions in individual countries.

In October of 2013 the Peasant Unity Committee (CUC) announced the redistribution of land last month to 140 indigenous and peasant families. The families were part of the largest violent eviction in the recent history of Guatemala in March 2011 when non-state actors, police, military forces and the government forced nearly 800 indigenous Q’eqchí families of their land without notice, destroyed their crops and burned their homes.

The evicted families, representing 14 ancestral communities who had been on the land for generations, suffered psychologically, socially and economically from the ordeal. These human rights violations show the state’s complicity with companies and landholders who exploit farmworkers and peasants.

Since the evictions in March 2011, private security members allegedly hired by the Utzaj Chabil Company began a chain of armed attacks, death threats, intimidation, persecution and criminalization against community leaders. Chabil Utzaj is a sugarcane company located in the fertile lands of Polochic Valley. The company wants to expand its sugarcane plantation in the area regardless of the human rights of the families who live there. To date, the community has suffered the assassinations of several peasant and indigenous leaders, including Antonio Beb, Oscar Reyes, María Margarita Che and Carlos Cucul Tot.

With the support of the Inter-American Development Bank, the Guatemalan government has been imposing a model of development that threatens the territory and the lives of Guatemalan indigenous communities. Human rights abuses of peasants and indigenous peoples, the loss of their land, and severe environmental destruction are happening in the name of the “green and clean” fuel production – one of the false solutions of the corporate “green economy.”

The indigenous Q’eqchi population has been repeatedly stripped of their land and territory through different historical processes promoted or authorized by the state. Today communities face the new challenge of the re-concentration of land in the hands of companies dedicated to large-scale monoculture plantations. This has led to a drastic reduction in indigenous communities’ access to land, limiting their ability to sustain their ways of life, and threatening food security.

Three months after the eviction of the 769 families, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued in June 2011 precautionary measures in favor of the families, ordering the State of Guatemala to provide food security and decent housing. But the government did not fulfill the international orders.

It was not until the ”Popular, Peasant and Indigenous Peoples March” in March 2012, that the government committed to resolve the land conflicts of the Polochic Valley, meet the Precautionary Measures and return the land to illegally evicted families. Organized by CUC and 15 other ally organizations, thousands of people marched to Guatemala City in defense of the land and territory. CUC used “La Marcha” to pressure the government to address the situation of the Polochic Valley families, as well as many other communities across the country affected by megaprojects such as mining and mega-dams.

Facing organized pressure from grassroots movements, the government has finally begun to honor the agreements it made in the wake of La Marcha. However, community leaders emphasize that there is still a long way to go. The legal land titles for the first 140 families are merely the first step in long overdue commitments. CUC and its allies in La Marcha continue to demand land for the remaining 629 Q'eqchí families, and call for decent housing, access to basic services, the legal review of the land grabbed by Chabil Utzaj company, and an end to the national promotion of African palm and sugarcane monoculture.

Waldemar Basilio Vazquez, an organizer with CUC, explains: “The Guatemalan government is repressing the people through militarization, favoring landholders, corporations and extractive companies against Guatemala peace accords ... repressing our sisters and brothers who are in resistance.”

A partner of Grassroots International, CUC is playing a key role in protecting the rights of rural families and indigenous groups, and making every effort to provide sufficient and suitable land to the displaced communities. Grassroots International supports CUC’s efforts and is in solidarity with all the Q’eqchí families in the Polochic Valley.

The Final Warning Bell

April 2, 2014 by juanbronson

In Brazil deforestation repesents 70% of the country’s carbon emissions (photo courtesy of the WWF)

The following was written by a compassionate person I'd like to call a friend who has been involved with many reforestation projects and other attempts to empower the people of the area by the name of Richard Bronson. His story alone is worthy of a book.

The final warning bell has been rung by a UN Climate Change report. The ongoing destruction of the remaining tropical rain forests and the advance of the pine beetle into the extreme north has contributed to 1/5th of the carbon being delivered into our precious atmosphere, much more than all the motorized vehicles, ships and factories on the planet. Agriculture is the main polluter and negative factor in this equation. Here in Guatemala, just to mention an example, at certain times of the year, the burning of the cane fields on the Pacific coast, is enough to darken the sky and cause an ash fall of choking dimensions in nearby communities.

The question is why has forestry not been able to play a more important and sustainable role in mitigating climate change? One obvious reply is that the global public is kept in the dark by a disinterested media, passive educators and politicians looking only as far as the next vote.

But then what about reforestation companies and the forest investment companies? Why are they not playing a greater role in the sequestration of carbon and so the salvation of our planet as we know it. Again the answer is painful: enormous areas covered by mono-cultures of short term tree crops for mainly pulp or biomass using species (e.g. Pine,Eucaliptus or Melina) that are most often foreign to the tropics with negative effects on the soil. Sustainable agroforestry is one answer. India has just passed more progressive legislation that removes many of the bureaucratic restrictions on the planting and use of new forests by farmers,that is expected to increase the forest cover there by millions of hectares. Both investors, forestry companies and governments need to pay more attention to native forest species for lumber and food while considering the infinite possibilities of sub-canopy planting.

In addition, especially Universities should be playing an important role in environmentally correct reforestation and habitat recovery, but sadly most often their endowment funds invest in mono-cultures and doubtful short term returns, while their scientists preach another story. It is a dysfunction that every responsible citizen and especially foresters need to urgently correct before we are obligated to send a flotilla of arks to Bangladesh, a country that lies almost entirely at sea level.

- Richard Bronson

Palm monoculture in Guatemala

This is a parcel of Richards property where he has introduced cacao among his teak plantation to expand the potentials of monoculture.

Barraclough, Solon L.; Scott,

Michael F. 1988. The Rich Have Already Eaten Roots of Catastrophe in Central

America. Pp 2-20, 23-25. The Kellogg Institute for

International Studies, Notre Dame.

Barry, Tom; Garst,

Rachel. 1990. Feeding the Crisis:

U.S. Aid and Food Policy in Central America. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Bebbington, Anthony; Thiele, Graham. 1993. Non-Governmental Organizations and the State

in Latin America. Pp 13-28, 60-74. Routledge, New York.

Brockett, Charles D.

1998. Land, Power, and Povery: Agrarian Transformations and Political Conflict in

Central America, second edition. Pp

1-128. Westview

Press, Boulder.

Burns, Bradford; Muybridge,

Eadweard.

1986. Eadweard Muybreidge in Guatemala, 1875. Pp 32, 100. The

University of California Press, Berkeley.

de Janvry,

Alain. 1981. The Agrarian Question and Reformism in Latin

America. Pp 200-223, 144-148,

211-213. Johns Hopkins University Press,

Baltimore.

de Janvry,

Alain; Dethier, Jean-Jacques. 1985.

Technological Innovation in Agriculture.

Pp 16-19, 56-45. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Geocities website. January 30, 2001. Overview of the threats of

deforestation, pictures and maps.

www.geocities.com/blancaveliz/Agriculture.htm ,

Accessed April 8, 2003.

Healy, Mark.

2003. Harper college website with

articles pertaining to

economic, and geographic conditions in specific countries and

regions. http://harpercollege.edu/~mhealyg101ilec/midamer/mme/mmelan/mmelenaa.htm , Accessed April 8, 2003.

Helwedge, Ann; Twomey, Michael J. 1991.

Modernization and Stagnation. Pp

121-140. Greenwood Press, New York.

McCreery, David. 1994.

Rural Guatemala 1760-1940. Pp

49-84, 295-322. Stanford University

Press, Stanford.

Rainforest education website. 2002. Pictorial overview of

threats to the rainforest.

www.rainforesteducation.com, Accessed April 8, 2003.

Reilly, Elena.

1999. Agribusiness and the Land

Crisis in Guatemala. An

overview of current and past patterns of land tenure in Guatemala.

http://cjd.org/paper/agri.html, accessed April 8, 2003

Tucker, Richard P.

2000. Insatiable Appetite. Pp 120-179.

The University of California Press, Berkeley.

Jovanna Garcia Soto

2000. Grassroots International

http://www.grassrootsonline.org/news/blog/140-indigenous-families-win-back-land-guatemala