This information was retrieved from Wikipedia, so for more links and information go online for the original.

The United Fruit Company (1899–1970) was a major American corporation that traded tropical (primarily bananas and pineapples) grown in Third World plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. Critics often accused the company of exploitative neocolonialism and described it as the archetypal example of the influence of a multinational corporation on the internal politics of the so-called "banana republics."

The United Fruit Company was known as la frutera ("the fruit company") or Mamita Yunay ("Mommy United") in Central America, where it was most active. For much of the 20th century, it dominated the exportation of bananas from Latin America and maintained a virtual monopoly on the banana trade in certain regions. The company had a deep and long-lasting impact on the economic and political development of several Latin American countries.

Corporate history

In 1871, U.S. railroad entrepreneur Henry Meiggs signed a contract with the government of Costa Rica to build a railroad connecting the capital city of San José to the port of Limón in the Caribbean. Meiggs was assisted in the project by his young nephew Minor C. Keith, who took over Meigg's business concerns in Costa Rica after Meiggs' death in 1877. As an experiment, Keith had begun planting bananas along the train route in 1873.

When the Costa Rican government defaulted on its payments in 1882, Keith had to borrow £1.2 million from London banks and from private investors in order to continue the difficult engineering project. In 1884, the government of President Próspero Fernández Oreamuno agreed to give Keith 800,000 acres (3,200 km²) of tax-free land along the railroad, plus a 99-year lease on the operation of the train route. The railroad was completed in 1890, but the flow of passengers proved insufficient to finance Keith's debt. On the other hand, the sale of bananas grown in his lands and transported first by train to Limón and then by ship to the United States, proved very lucrative. Keith soon came to dominate the banana trade in Central America and in the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

In 1899, Keith lost $1.5 million when the New York City broker Hoadley and Co. went bankrupt. He then travelled to Boston, Massachusetts, where he arranged the merger of his banana trading concerns with the rival Boston Fruit Company. Boston Fruit had been established by Lorenzo Dow Baker, a sailor who, in 1870, had bought his first bananas in Jamaica, and by Andrew W. Preston. The result of the merger was the United Fruit Company, based in Boston, with Preston as president and Keith as vice-president. Preston brought to the partnership his plantations in the West Indies, a fleet of steamships (the "Great White Fleet"), and his market in the U.S. North-East. Keith brought his plantations and railroads in Central America and his market in the U.S. South and South-East. At its founding, United Fruit was capitalized at $11,230,000.

In 1901, the government of Guatemala hired the United Fruit Co. to manage the country's postal service. By 1930, the Company had absorbed more than 20 rival firms, acquiring a capital of $215,000,000 and becoming the largest employer in Central America. In 1930, Sam Zemurray (nicknamed "Sam the Banana Man") sold his Cuyamel Fruit Co. to United Fruit and retired from the fruit business. In 1933, concerned that the company was mismanaged and that its market value had plunged, he staged a hostile takeover. Zemurray moved the company's headquarters to New Orleans, Louisiana, where he was based. United Fruit went on to prosper under Zemurray's management; Zemurray resigned as president of the company in 1951.

Corporate raider Eli M. Black bought 733,000 shares of United Fruit in 1968, becoming the company's largest shareholder.

In 1969 Zapata Corporation, a company in which George H. W. Bush held significant interest, acquired a controlling interest in United Fruit. The president of Zapata was Robert Gow, a friend of the Bush family. Robert's father, Ralph Gow, was on United Fruit's board of directors.

In June 1970, Black merged United Fruit with his own public company, AMK (owner of meatpacker John Morrel), to create the United Brands Company. United Fruit had far less cash than Black had counted on and Black's mismanagement led to United Brands becoming crippled with debt. The company's losses were exacerbated by Hurricane Fifi in 1974, which destroyed many banana plantations in Honduras. On February 3, 1975, Black committed suicide by jumping out of his office on the 44th floor of the Pan Am Building in New York City. Later that year, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission exposed a scheme by United Brands to bribe Honduran President Oswaldo López Arellano with $1.25 million, and the promise of another $1.25 million upon the reduction of certain export taxes. Trading in United Brands stock was halted and Lopez was ousted in a military coup.

After Black's suicide, Cincinnati-based American Financial, one of millionaire Carl H. Lindner, Jr.'s companies, bought into United Brands. In August 1984, Lindner took control of the company and renamed it Chiquita Brands International. The headquarters was moved to Cincinnati in 1985.

Throughout most of its history, United Fruit's main competitor was the Standard Fruit Company, now the Dole Food Company.

History in Central America

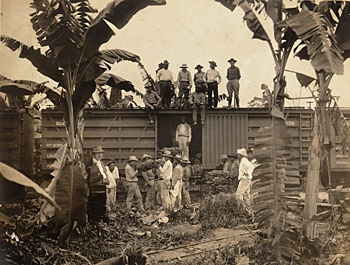

The United Fruit Company (UFCO) owned vast tracts of land in the Caribbean lowlands. It also dominated regional transportation networks through its International Railways of Central America and its Great White Fleet of steamships. In addition, UFCO branched out in 1913 by creating the Tropical Radio and Telegraph Company. One of the company's primary tactics for maintaining market dominance was to control the distribution of banana lands. UFCO claimed that hurricanes, blight and other natural threats required them to hold extra land or reserve land. In practice, what this meant was that UFCO was able to prevent the government from distributing banana lands to peasants who wanted a share of the banana trade. The fact that the UFCO relied so heavily on manipulation of land use rights in order to maintain their market dominance had a number of long term consequences for the region. For the company to maintain its unequal land holdings it often required government concessions. And this in turn meant that the company had to be politically involved in the region even though it was an American company.

UFCO had a mixed record on promoting the development of the nations in which it operated. In Central America, the Company built extensive railroads and ports and provided employment and transportation. UFCO also created numerous schools for the people who lived and worked on Company land. On the other hand, it allowed vast tracts of land under its ownership to remain uncultivated and, in Guatemala and elsewhere, it discouraged the government from building highways, which would lessen the profitable transportation monopoly of the railroads under its control.

The Guatemalan government of Colonel Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán was toppled by covert action of the United States government in 1954, after the directors of UFCO had lobbied to convince the Truman and Eisenhower administrations that Colonel Arbenz intended to align Guatemala with the Soviet bloc. Besides the disputed issue of Arbenz's allegiance to Communism, the directors of UFCO may have feared Arbenz's stated intention of purchasing uncultivated land from the company (at the value declared in tax returns) and redistributing it among Native American peasants. The American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was an avowed opponent of Communism whose law firm had represented United Fruit. His brother Allen Dulles was the director of the CIA. The brother of the Assistant Secretary of State for InterAmerican Affairs John Moors Cabot had once been president of United Fruit. (Though, the U.S. had harbored suspicions about Arbenz prior to the Dulles brothers' appointments. ) Arbenz's government was overthrown by Guatemalan army officers invading from Honduras, with assistance from the CIA (Look up Operation PBSUCCESS online).

Ironically, the operation failed to benefit the company despite the new regime. The company's stock market value declined along with its profit margin. The Eisenhower administration proceeded with anti-trust action against the company, which forced it to divest in 1958. In 1972, the company sold off the last of their Guatemalan holdings after over a decade of decline.

Company holdings in Cuba, which included sugar mills in the Oriente region of the island, were expropriated by the 1959 revolutionary government led by Fidel Castro. By April 1960 Castro was accusing the company of aiding Cuban exiles and supporters of former leader Fulgencio Batista in initiating a seaborn invasion of Cuba directed from the United States. Castro warned the U.S. that "Cuba is not another Guatemala" in one of many combative diplomatic exchanges before the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961. Despite significant economic pressure on Cuba, the company were unable to recoup cost and compensation from the Cuban government.

Reputation

The United Fruit Company was frequently denounced by leftist leaders and intellectuals, who accused it of bribing government officials in exchange for preferential treatment, exploiting its workers, contributing little by way of taxes to the countries in which it operated, and working ruthlessly to consolidate monopolies. Latin American journalists sometimes referred to the company as el pulpo ("the octopus"), and leftist parties in Central and South America encouraged the Company's workers to strike. Latin American writers Carlos Luis Fallas of Costa Rica, Miguel Ángel Asturias of Guatemala, Gabriel García Márquez of Colombia, and Pablo Neruda of Chile, all denounced the Company in their literature.

The business practices of United Fruit were also frequently criticized by journalists, politicians, and artists in the United States. Little Steven released a song called "Bitter Fruit" about the company's misdeeds. In 1950, Gore Vidal published a novel (Dark Green, Bright Red), in which a thinly fictionalized version of United Fruit supports a military coup in a thinly fictionalized Guatemala. This reputation for malfeasance, however, was somewhat offset among those who worked for it or in the regions it controlled by the Company's later efforts to provide its employees with reasonable salaries, adequate medical care, and free private schooling. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Company and its successor, United Brands, created an Associated Producers Program that sought to transfer some of its land holdings to private growers whose produce it commercialized. As the Company gradually lost its land and transportation monopolies, its status as a capitalist bête noire declined.

Today, successor companies of United Fruit have interests in Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama.

Diane K. Stanley wrote a book called "For the Record: The United Fruit Company's Sixty-six Years in Guatemala" which explores the concerns and criticisms of the United Fruit Company. In the preface, Stanley explains:

"Few American companies operating in Latin America have been more consistently criticized than the United Fruit Company. Incorporated in New Jersey in 1899, the Boston-based banana company at one time owned or leased approximately 3.5 million acres in Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Colombia and Ecuador. In its peak years, during the 1930s, United Fruit employed upwards of 100,000 persons, more than 90 percent of whom were Latin Americans. Nowhere has the Company been more castigated than in Guatemala, where it began its operations in 1906, and sold its last holdings to the Del Monte Corporation in 1972. Historians, economists, journalists, politicians, lawyers and others -- both American and Guatemalan -- have written extensively about the United Fruit Company, usually in disparaging terms. In the 1950s, even Miguel Angel Asturias, Guatemala's Nobel Prize-winning novelist, wrote a bitter trilogy censuring the Company.

Most of the literature, particularly books and articles written by Guatemalans who participated in the revolutionary "ten years of spring" which the country experienced between 1944 and 1954, was published thirty to forty years ago. In the interim, the unremitting violence that has afflicted Guatemala for the last three decades -- some of which has been directed at scholars, regardless of their ideological persuasions -- has made Guatemalan historians extremely reluctant to analyze the ten years of the Arévalo/Arbenz administrations or that of succeeding governments. There is, therefore, a notable dearth of books by Guatemalan scholars who might have written more objectively about this convoluted period of their country's history.

Nearly all recent histories of Guatemala by North American scholars, however, continue to exploit the establishment's prevailing views of the United Fruit Company (today's Chiquita Brands International). These historians repeat the same negative assertions -- many of which are untrue or have been distorted. As a result, a "black legend" has evolved that holds UFCO responsible for a long list of nefarious practices, chief of which are a constant, reprehensible interference in the nation's politics, the ruthless exploitation of its workers, and the extraction of millions of dollars in profits, while contributing virtually nothing to Guatemala's development.

Having been born at a United Fruit Company hospital on Guatemala's north coast and lived for several years in the division headquarters for its south coast plantations, I have always found it curious that so many scholars have consistently repeated the same accusations about UFCO's Guatemala operations. It is even more intriguing that virtually no historians have sought to verify whether most of the oft-repeated charges are, in fact, valid. This book, which does not pretend to be an academic treatise, puts on the record essentially all of the criticisms that have been published about the United Fruit Company's tenure in Guatemala. While some of the allegations are certainly valid, it is also apparent that many others are completely erroneous -- as only a few authors have thus far pointed out. Not surprisingly, U.S. scholars have largely dismissed these writers as "apologists."

Most accounts about the banana company have also failed to describe the significant contribution that United Fruit made to Guatemala's human and economic development. In addition to providing employment to tens of thousands of workers and paying them the nation's best rural wages, the Company also offered its employees excellent medical care, rent-free housing, and six years of free schooling for countless children. By clearing and draining thousands of acres of jungle that are today among the country's most productive farm lands, United Fruit converted Guatemala into a major banana producer, thereby ending the country's unhealthy dependence on its exports of coffee. The Company's pioneering work in eliminating malaria and other tropical diseases early in the twentieth century also demonstrated that Guatemala's sparsely inhabited coastal areas offered rich, previously unexploited agricultural zones. Ultimately, the taxes and salaries that the United Fruit Company paid, and the millions of dollars of foreign exchange earnings that it annually generated, impacted in an important way on Guatemala's economy.

The book also examines the frequently repeated charge that the United States engineered the 1954 coup against the government of President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán in order to regain the land Guatemala had expropriated from the United Fruit Company. Although UFCO was certainly instrumental in orchestrating an effective media campaign against the Arbenz government, it is clear that the Eisenhower administration was intent on ousting what it considered to be a Communist beachhead that threatened U.S. national security. Spurred on by John Foster Dulles, his vehemently anti-Communist secretary of state, President Eisenhower would have moved to depose Arbenz even if the United Fruit Company had never operated in Guatemala.

Finally, the book provides little-known information about the enormous effort that was required to establish immense banana plantations in the midst of isolated jungles, where health concerns and the oppressive heat were constant, debilitating factors. While United Fruit's complex and efficient division of labor was undoubtedly instrumental in transforming huge wilderness areas into productive farm lands, it was the employees -- Guatemalan, North American and European -- whose hard work made possible the conquest of Guatemala's disease-ridden coastal areas. In doing so, those rugged individuals and their families were forced to cope with the extreme isolation and overwhelming tedium that characterized life on a banana plantation. That they were able to do this, particularly early in the twentieth century, is a remarkable feat that has been little understood or recognized."

Santa Marta Massacre

- Further information: Santa Marta Massacre, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán

One of the most notorious strikes by United Fruit workers broke out on 12 November 1928 on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, near Santa Marta. Historical estimates place the number of strikers somewhere between 11,000 and 30,000. On 6 December, Colombian Army troops under the command of General Carlos Cortés Vargas opened fire on a crowd of strikers gathered in the central square of the town of Ciénaga. The military justified this action by claiming that the strike was subversive and its organizers Communist revolutionaries. The number of people killed in that incident is disputed: General Cortés himself estimated that 47 people had died, but Liberal Party congressman Jorge Eliécer Gaitán claimed that the toll was much higher and that the army had acted under instructions from the United Fruit Company. The ensuing scandal contributed to President Miguel Abadía Méndez's Conservative Party being voted out of office in 1930, putting an end to 44 years of Conservative rule in Colombia. The first novel of Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, La Casa Grande, focuses on this event, and the author himself grew up in close proximity to the incident. The climax of García Márquez's novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is based on the events in Ciénaga, though the author himself has acknowledged that the death toll of 3,000 that he gives there is greatly inflated.