The ancient Maya proved themselves no exception to this human need

to give shape to the universe.

Everything we know about the ancient Maya comes from their as yet

indecipherable four Codices, their cryptic architectural inscriptions, the

tainted practices of their modern descendants, and the writings of culturally

prejudiced Spanish colonists. Our picture of their world view is incomplete

and open to interpretation. Most scholars agree that the Maya philosophy

answered most of the fundamental questions of the universe by integrating

their arithmetic, their astronomical measurements, their view of time as

essentially cyclical, and their pantheon of gods. The Maya used science to

validate their faith. The Maya saw science, especially astronomy, as an

instruments for unearthing spiritual truth and reading the divine prophecies

written in the night sky.

This harmony between science and religion is evident in the duties

and functions of the ancient Mayan priests, the Ah Kinob. Astronomy and

mathematics at the heart of Mayan philosophy were "priestly" inventions,

and theologists of the Maya civilization also served as its scribes,

mathematicians, astronomers, and intellectuals.

The Nine Mayan Gods (Bolontiku) are the principle deities having

dominion over the area of Central America from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

to the Isthmus of Panama. To the indigenous people of the Mayan area, the

Bolontiku have historically fulfilled a cultural role with their power, wisdom,

sanction and protection were invoked for all earthly and spiritual transactions

– for healing, divination, success in agriculture, trade, politics and

war; for help in personal matters such as love, childbearing, grief; for

carrying (telepathic) messages over distance; and so on.

Sophisticated mathematics allowed the Ah Kinob to conceive of a

universe regular in its rhythms. In its simplicity, the Mayan number system

employed only three characters - a dot symbolizing unity, a bar representing

the number five, and an eye-shaped glyph representing zero. Mayan numbers

were written vertically and divided into tiers, with the characters in each

tier of the column having a value twenty times that of the characters in

the tier directly beneath them. Summing the values of the tiers yielded the

number represented in the glyph. Dispensing entirely with fractions, the

Maya expressed all non-integer quantities in terms of ratios or

equivalencies.

Two exceptional features of the Mayan mathematics - the use of zero

and the assignment of value by position - made this system the most advanced

of its time. The Hindus, once thought to be the original discoverers of zero

and the position convention, developed them a thousand years after the Maya.

This allowed the Mayans to reconcile their various calendrical systems and

compile lists of multiples for use in reckoning the periods of astronomical

events, as well as keep accurate records of governmental and commercial

transactions.

Mayan religion pervaded all aspects of daily life. The rituals the

priests prescribed, the holidays the Maya celebrated, the idols they venerated,

even their dietary habits - in short, the pulse of Mayan life-were all religious

in origin. Every material object in the Maya world, as well as every moment

in time, had divine worth and godly significance. Additionally, the interplay

between rival gods and between the gods and humankind supposedly manifests

itself in daily occurrences.

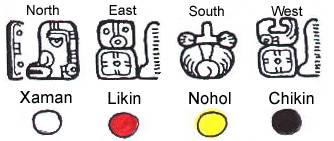

The Maya conceived of the world as flat and four cornered, with the

directions of the four corners lying approximately in between the cardinal

directions . Each corner had a characteristic color; the north's color was

white; the south's, yellow; the east's, red; and the west's, black.

Bacab (plural Bacabs) of the Four Directions:

Mulac: North,

Cauac: South,

Kan: East,

Bacab West

Green was the characteristic color of the earth's center. According

to the Mayan model, the earth spins around a central axis consisting of a

huge ceiba tree called the Wakah-Chan, or "World-Tree", whose trunk extends

into the heavens toward the North Star and whose roots delve deep below the

plane of the earth. The heavens themselves rotate around this axis as a giant

celestial sphere, making the Mayan model of the Earth highly reminiscent

of a spinning gyroscope.

The Mayan model holds that Earth is but one of three coexisting

universes: the Upperworld, the Underworld, or Xibalba, and the human or concrete

world . Unifying these three planes, the World Tree serves as a portal between

the human world and the other two worlds through which gods pass freely.

Four Bacabs, or Atlases, support the plane of the Earth from below; in turn,

four giant ceiba trees located at each corner of the world hold aloft the

Upperworld, which hovers over the plane of the earth during the daytime.

Most of the benevolent gods in the Maya pantheon, called oxlahuntiku, inhabit

the Upperworld, which the lofty branches of the World Tree divide into thirteen

levels. The Underworld, situated below the plane of the earth, is a grim

place of darkness and decay very similar to the Mesopotamian land of the

dead. Evil gods known collectively as the Lords of Death or bolontiku, the

bearers of drought, hurricanes and war, dwell in the nine levels of the

Underworld.

The Maya believed that at night these celestial planes rotate around

the earth's axis, giving human observers a view of the Underworld and temporarily

concealing the Upperworld. Some scholars submit the more popular opinion

that the celestial sphere is fixed in place, and that the sun travels through

the subterranean Underworld at night to reemerge from the earth at dawn.

In this view, each day is a cycle of destruction and rebirth, as the Maya

believed that the world could be symbolized by a giant reptile that devours

and regurgitates the sun at sunset and sunrise, respectively. Kinh, the sun

god, emerges from the maw of the earth in the morning, ascends through the

thirteen levels of heaven, arriving at the uppermost level at noon, and descends

once more through the Upperworld to reenter the Underworld at dusk. Thus,

kinh unites the three worlds of the Maya faith.

Aside from the giant Earth Monster, the Maya texts also present the

human plane as the back of a giant turtle, or a crocodile resting in a pool

of lilies. These creatures hold symbolic importance to the Maya, and appear

frequently in their zodiac and in their manuscripts. The "Earth-Monster's"

counterpart in the Upperworld is a long serpentine creature, the "Cosmic

Monster," who sheds his blood in the form of rain to replenish the parched

earth. No animalistic representative of Xibalba, the Underworld, was found

in the literature.

A multitude of deities governed the Maya universe. In addition to

patron gods of cities and kingdoms, the Maya revered gods for every profession

from beekeeping to hunting; gods for days, months, years, and epochs; gods

for emotions; gods for objects animate and inanimate; and gods of noble families.

So many gods existed for seasons of the year, days of the week, and other

calendrical events that the Maya faith has been called a "solar and temporal

cult". Many of the more widely worshipped deities had four constituent gods

representing each corner of the world; some even had Underworld counterparts

and female partners, in keeping with the dualistic theme of the Maya faith.

At least one hundred and sixty six major gods received homage from the Maya

priests and figure prominently in texts such as the Codices and the Popol

Vuh; it is likely the Maya worshipped a plethora of other gods on an informal

basis.

THE GODS OF THE UNDERWORLD

Each of the Nine Gods of the underworld has his or her own specialty

(there are four female deities and five males). The Bolontiku communicate

with their votaries through what we would call channeling and prophetic dreams,

which to the Maya were as much a part of everyday life as the telephone and

television are to us. A dream prompted by the Bolontiku can be distinguished

from a normal dream by the invariable presence of one personage who says

nothing but who stands in the background of whatever scene is unfolding.

Upon awakening the dreamer realizes that this mute personage was actually

inducing and directing the entire experience, and is in fact one of the Nine

revealing a message of importance. Non-Mayans do not necessarily see the

Bolontiku as Mayans: to my benefactor they appear (in dreams) as long-haired

hippies; and when they have appeared to me they come in three-piece suits.

The city of Tikal, located in the remote jungle of northern Guatemala,

was (and is) the sacred home city of the Bolontiku. Abandoned mysteriously

a thousand years ago, the jungle swallowed it up until its excavation by

the University of Pennsylvania fifty years ago (see National Geographic magazine

December 1975 issue). These archeological ruins are now part of a national

park-cum-nature preserve administered by the Guatemalan government.

The Bolontiku themselves are delighted to see their sacred city restored

to at least part of its former grandeur. There is the spectacle of immense

pyramids and plazas set in the midst of impenetrable jungle teaming with

exotic birds, howler monkey and jaguars. Moreover, the Nine promise to give

a valuable lesson to any visitor to Tikal who wishes to invoke

them.

The cult of the Nine Mayan gods has fallen into general neglect among

the Maya. At the same time, the fragile ecosystem of the Mayan area has been

and is being threatened by the destruction of massive tracts of tropical

rainforest. As a result, the Bolontiku have been calling foreigners in to

revive their cult, to publicize their ecological concerns, and to buy up

and preserve as much virgin rainforest as possible.

In front of this pyramid there is a row of eight steles, with a ninth

stele in front of the row of eight. Before each stele is a squat, cylindrical

altar

Ah Puch - God of death and ruler of Mitnal, the lowest and most terrible

of the nine hells. Portrayed as a man with an owl's head or as a skeleton

or bloated corpse. Also known as 'God A'. Ah Puch survives in modern

Mayan belief as Yum Cimil (Lord of Death).

In Mesoamerican myth, Au Puch, also known as Yum Cimil and Cum Hau,

is the Mayan Lord of the dead. His realm is Hunhau, which literally means

"spoil." It is a bitter land of the dead where punishments are inflicted

on evil doers. Au Puch presides over the ninth and worst layer of Hunhau.

He is usually depicted as a skeleton (skull head, bare ribs and spiny projections

from the vertebrae) or with bloated flesh marked by dark rings of decomposition

and a menacing grin. In his hair are bell like jewelry and he takes great

pleasure in causing eternal torture and torment to the damned. According

to some legends, he is said to occasionally roam the earth looking for evil

people, causing war, sickness, and death. Once someone is condemned to Hunhau,

they can never leave. Sacrificial victims were offered to Au Puch in the

cenote or sacred pool.

Ahau-Kin - Called the 'lord of the sun face'. The god of the

sun, he possessed two forms - one for the day and one at night. During the

day he was a man with some jaguar features, but between sunset and sunrise

he became the Jaguar God, a lord of the underworld who travelled from west

to east through the lower regions.

Ah Uuc Ticab - Deity of the underworld

Bolon Ti Ku - Underworld Deity

Chamer - Mayan god of death in eastern Guatemala. His consort is

Xtabai

Cizin - God of death. He burns the dead in the Mayan underworld.

Cizin is the Mayan god of death. His name literally means "stench." He is

described as having a fleshless nose and lower jaw. Sometimes his entire

head may be depicted as just a skull. He wears a "collar with death eyes

between the lines of hair, and a long bone hangs from one earlobe." (Jordan,

57) Cizin's body may be shown as a spine and ribs or it can be painted with

black and yellow spots, which are the Mayan color of death. He resides in

Tnal, the Yucatec place of death. His primary job is to burn the souls of

the dead. The soul of the deceased is first burned on the mouth and anus

by Cizin. When the soul complains, Cizin will douse it with water until the

soul complains again. The soul is then burned until there is nothing left.

The next stop is to the god, Sucunyum, who spits on it's hands and cleanses

it, after which the soul is free to go where it chooses.

Cum Hau - Mayan god of death.

Hanhau - Underworld Deity, Mitnal

Hun Came - Quiche Maya co-ruler of Xibalba, the Mayan underworld.

In the Popol Vuh creation myth he murdered Hun-Hunapu and Vukub-Hunapu.

Subsequently he and his co-regent Vukubcame were destroyed by Hunapu and

Xbalanque.

Hun-Hunapu - In the Quiche Maya Popol Vuh creation myth, Hun-Hunapu

was the divine twin of Vukub-Hunapu. They were the sons of Xpiyacoc and Xmucane.

The two were murdered in a ball game by the two rulers of Xibalba, the Mayan

underworld. They were avenged by Hun-Hunapu's children Hunapu and Xbalanque.

MAYAN CONCEPT OF CREATION: At the beginning, there was nothing. Then

came the creator, Tepeu and Gucumatz, one but at the same time, two. They

are surrounded by clarity,which represents the Holy Spirit, therefore, the

Trinity. In scientific terms these three forces could be called positive,

negative, and neutral. In other words: Ying, Yang, and Tao. Every culture,

at a certain stage of development, seems to describe the creation of the

universe in similar terminology.There seems to be a basic truth, a unified

principle, which somehow evolved in more than one culture around the

world.

There are nine Bolontiku or nine Lords of the Underworld. In

the Dark Ages of the mayan Empire these nine gods ruled over all, each one

for a day and rotating their power in succession in the same way the planets

succeed each other in our week of seven days.

THE DWARF: There exists the belief that witches have instruments

of evil called Ikal that come out at night to harm people, in some cases

even causing death. The Ikal is sometimes depicted as a hunchbacked dwarf

dressed as a priest. Presumably this symbolizes the fear of the white man

who conquered the Mayans five hundred years ago.

THE FROGS: According to Mayan mythology, when a frog croaks it is

calling for rain. Thus, four frogs are used in the ancient rain ceremony

each one summoning the god, Chac from a different direction of the

sky.

THE TURTLE: In Mayan mythology, it is said that if a turtle appears

in your path during a drought it is a sign of impending rain because the

turtle is also seeking water. It is also believed that the shell of the turtle

is a map of the universe.

The Indians with the long hair and the white flowing robes seen in

the jungle are the Lacadons, the last remnants of the ancient Mayan Empire

who fled to the jungle when the Spanish conquerors arrived. They have yet

to be assimilated into modern society.

THE DIALECTS: The Lacadones speak a dialect called Carebbean,

which is similar to the Mayan tongue spoken by the Diviner. The men and women

wearing black mantas speak Tzeltal. All three dialects have their roots in

the ancient Mayan language.

NUMBERS: Cabalistic numbers become the moving force of the events:

CYCLE OF 13 DAYS

In spite of the fact that their mathematical system was vigesimal,

the Maya counted the days also by fives, thirteens and twenties. They gave

numbers from 1 up to 13 to series of 20 day names in a continuous cycle.

These thirteens are so important, that we have to devote a special chapter

to them. In the manuscripts we can find cycles which are multiples of 13,

for example, 26, 52, 65, 78, 91, 156, 182, 208, 234, 260 etc.

At each moment, the resulting force of all these magic numbers

interacting

First there was nothing. The expanse of the sky was empty. All motionless

silence in the darkness, in the night. Only the creator Tepeu, Gucumatz,

the Progenitors were there in the water surrounded with clarity.

Then there was the word. Tepeu and Gucumatz came together in the

darkness, in the night, and talked to one another. It became clear, as they

meditated, that when the dawn came man should appear. Thus it was disposed

among the shadows and in the night by the Heart of Heaven who is called Huracan.

The first account of the Popul Vuh Synopsis An isolated village in

the highlands of Mexico is suffering a severe drought. The local Shaman,

consults his oracle, drinks the villagers' posh and predicts rain. He proceeds

to pass out drunk.The villagers plant their crops, but the rain does not

come. A comet traverses the sky and the villagers fear it to be a bad omen.

That night the Cacique (village chief) meets with the village council. They

all agree that their Shaman has lost his powers and has forgotten how to

talk to the Gods. Some mention another man who could help them, a solitary

Diviner who lives in the mountains and still knows the ways of the Ancients.

The Cacique believes he's a witch and won't allow a witch roaming his village

while he's in charge. He boasts of his contact with the white man, an engineer

he once met. He insists that the old ways no longer work, that they should

consult the white man's methods instead. He produces a flashlight from under

his chamarra and shines his flashlight in the group's face, as if to prove

his point; then he leaves. The next day a startled Cacique is awakened by

the blare of a horn, signaling a summons to a meeting with the village elders.

He dresses in a rush, as his two wives and an old woman watch him with vacuous

eyes. As he leaves he see the comet again traversing the morning sky. At

the reunion with the grandfathers, again he is told of the Diviner. The elders

believe that only the diviner can summon Chac, the Rain God. They instruct

him to round up his twelve captains and go find the wise man. This time the

Cacique does not argue. He leads his group of captains up a steep mountain,

while a mute boy, the son of one of the captains, spies their departure from

behind a wall.After an arduous climb they reach the Diviner's dwelling. The

Diviner seems to be waiting for them and invites them in. He then surprises

everyone by asking the mute boy, who had been following all along, to emerge

from behind the bushes. He instructs the boy to go prepare pozale, the local

meal. From a large gourd the mute boy distributes pozale among the men under

the watchful eye of the Diviner. When it is his turn, the Cacique greedily

gulps down three large servings, while the Diviner studies him intently.

The Diviner knows that the Cacique is skeptical,yet he agrees to help them.They

set out on a strange journey, which takes them far away from their own land

into the deep jungle. There the Diviner recruits the help of some very strange

men (the Lacandons) who carry the group in canoes across a lake. At every

turn the Chief and two of his captains grow more suspicious, fearful and

rebellious. At night, around the fire, the Diviner tells a haunting story,

the myth of the Twins, the Lords of Light who, through the use of magic and

deception, destroy forever the Lords of Darkness. By the end of the long,

hypnotic tale, only the mute boy remains awake. As the Diviner meditates

his spirit enters a hawk that transports him through the night to ancient

temples. There he connects with the knowledge of his ancestors.The next day

they come to a rushing torrent. Without hesitation the Diviner walks into

the water and proceeds to cross over the top of a treacherous waterfall.

To everyone's amazement he does not sink, nor is he swept away. Immediately

the mute boy follows. Most of the men fearfully go along too. But the Cacique

and his two loyal captains, who have no faith in the Diviner, have had enough

and refuse to cross the water. Instead they turn back and run away. The remaining

men

Follow the Diviner into a deep cave where they find "the Mother of

Waters", the original Spring,whose water they will use to invoke the Chac

in their ceremony.They return to the village without the Cacique and begin

elaborate preparations for the ceremony.The Diviner assigns tasks. He asks

an old woman to make sacred mead, a young one to gather the choicest ears

of corn, another to collect the purest honey and the mute boy to care for

the ceremonial fire. Men make masks, cut wood and build four high platforms,

one for each corner of the sky, where four dancers will enact the four Chacs.

The Cacique returns and spies the proceedings from a hilltop above the village.

He then slips to his hut, grabs his rifle and runs to the shaman to ask for

help. The Shaman says that he's come too late, that there is nothing he can

do.That night in the wild the Cacique encounters his Ikalin the form of a

midget priest who apparently terrifies him to death. At night in the village

all are gathered around a giant bonfire. The Diviner commences a chant of

invocation to summon the Gods of Rain. Soon the whole village is chanting

in unison. All night long the power of their voices flows like a river over

hilltops and through valleys. At dawn, clouds move towards the village and

fog envelops the crowd. The villagers believe that the rain has finally arrived.

They jump up, embrace one another and cheer. But a gust of wind whistles

through and skies clear again. An exhausted Diviner announces to the stunned

crowd that Chac will not come until three days have passed. Then he departs

in the direction of the mountains. The mute boy tries to follow him, but

the Cacique reappears and bars his way with his rifle.The following day,

while working the cornfield, the mute boy passes out and becomes ill. The

shaman examines him and announces that the boy has been possessed by the

Diviner's witchcraft. The boy's mother talks to those comforting her about

how a Shaman once said her son was born mute so he would keep God's secrets.

The boy utters "the fire" before he dies. The village council hastily meets.

The Cacique rants that the Diviner has tricked them, that he has only brought

evil to the village, but no rain. The boy's father demands vengeance. Another

member fears that more evil will come to them if they harm the Diviner. But

the Cacique explains that their Shaman said to drop the Diviner's body down

a deep well to drown his evil spirit. An older captain reminds everyone that

the Diviner said that rain was to come in three days and only two days had

passed. The cacique allows one more day for the rain to come. After that,

they will go kill him.Next morning, the rain still has not arrived. As the

group departs towards the mountain the three older captains again try to

dissuade the others from committing murder. But the Cacique and the rest

of the men ignore their pleas. Meanwhile, on top of the mountain, the Diviner,

while cleansing his body inside a sweat lodge, has a vision. When the villagers

arrive at the Diviner's dwelling the cacique silently sneaks in with his

rifle. He spots a hammock with someone in it and shoots. The rest of the

men rush in to see. Blood drips onto the Cacique's feet. He opens the hammock

and they are shocked to see that the Diviner has cut out his own heart as

a sacrifice. They bundle up his body in a hurry and throw it off a deep cliff

into the well. The body hits the water and a moment later drops of rain begin

to fall, lightly at first, then torrential. The men scatter away while the

cacique remains alone by the edge of the well screaming madly in the pouring

rain.

|