If someone were to ask you what is the most dangerous creature on earth that have been responsible for killing more people than all the wars in history? What would your answer be? ithout question the answer is: the mosquito. Mosquitoes and the diseases they spread . Even today, mosquitoes transmitting malaria kill 2 million to 3 million people and infect another 200 million or more every year. Tens of millions more are killed and debilitated by a host of other mosquito-borne diseases, including filariasis, yellow fever, dengue and encephalitis.

But for millions of Americans, malaria is something other people get somewhere else. The fact is that nearly half of the world’s population is at risk for malaria. Residents of the United States are not immune. Malaria has occurred in the United States, and still does on rare occasions. Mosquitoes capable of carrying and transmitting malaria still inhabit most parts of this country. And an influx of malaria-infected persons has produced localized malaria transmission in some areas of the United States.

Today, however, the threat of developing encephalitis from mosquitoes is far greater than the threat of malaria in many countries. Encephalitis, meningitis and other diseases can develop from the bites of mosquitoes infected with certain viruses. These include the viruses of West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis, LaCrosse (California) encephalitis, and Eastern equine and Western equine encephalitis.

THE MOSQUITO

THE MOSQUITO

Mosquitoes belong to the group of insects known as diptera, or flies. In fact, mosquito means “little fly” in Spanish. Diptera means “two wings” – the characteristic that distinguishes flies from other types of insects. What distinguishes a mosquito from other types of flies are its proboscis (long tubular mouthparts for sucking up fluids) and the hair-like scales on its body. They are most active when the temperature ranges between 65 and 80 degrees.

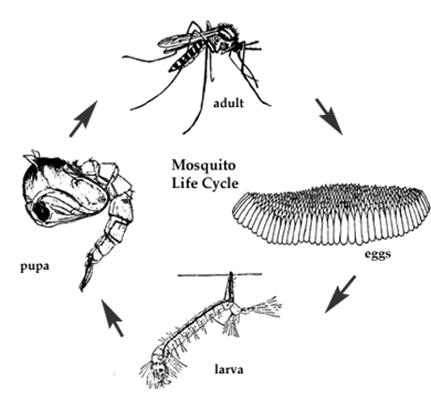

The female mosquito’s life is often measured in weeks or months. Males typically live only about a week. The immature stages of the mosquito are less familiar to us. Mosquitoes hatch from eggs laid in places that are or will be filled with water. The eggs hatch into worm-like larvae that usually lie just beneath the water’s surface, breathe through tubes on the tail end of their bodies, and feed on microscopic organisms, such as bacteria. Thus most mosquito larvae require water containing organic material, such as leaves or sewage to serve as food for microorganisms that will be consumed by the developing mosquito larvae.

In less than a week, hatchling larvae can grow and develop into comma-shaped pupae. While larvae are commonly called “wigglers” because they wiggle violently when disturbed, mosquito pupae are known as “tumblers” because they tumble through the water when disturbed. While mosquito larvae and pupae breathe through siphon-like devices, the pupal stage does not feed. Usually within three days the pupa will transform into an adult mosquito.

In less than a week, hatchling larvae can grow and develop into comma-shaped pupae. While larvae are commonly called “wigglers” because they wiggle violently when disturbed, mosquito pupae are known as “tumblers” because they tumble through the water when disturbed. While mosquito larvae and pupae breathe through siphon-like devices, the pupal stage does not feed. Usually within three days the pupa will transform into an adult mosquito.

There are some notable exceptions to the standard mosquito life cycle. The larvae of some mosquito species eat the larvae of other species, though the predatory larvae of some species will develop into blood-feeding adults.

Female mosquitoes can be particular about whose blood they consume, with each species having its own preferences. Most mosquitoes attack birds and mammals, though some feed on the blood of reptiles and amphibians. Only female mosquitoes bite, because a blood meal is usually required for egg laying. All male mosquitoes, and the females of a few species, do not bite. They feed on nectar and other plant juices instead of blood.

Various clues enable mosquitoes to zero in on people and other animals they seek to bite. They can detect carbon dioxide exhaled by their hosts many feet away. Mosquitoes also sense body chemicals, such as the lactic acid in perspiration. Some people are more attractive to mosquitoes than others. A person sleeping in a mosquito-infested room may wake up with dozens of mosquito bites, while the person sleeping next to them has none. Similarly, people react differently to mosquito bites, some showing very little sign of being bitten, while others exhibit substantial redness, swelling and itching. This is an allergic reaction to the mosquito’s saliva, the severity of which varies among individuals.

Mosquitoes can fly long distances; some more than 20 miles from the water source that produced them. But they don’t fly fast, only about 4 miles an hour. And because they typically fly into the wind to help detect host odors, fewer mosquitoes are about on windy days.

As a mosquito flies closer to its target, it looks for the movement of dark objects. Once it finds you, it lands, inserts its proboscis and probes for blood vessels beneath the skin. When it finds one, it injects saliva into the wound. The saliva contains an anticoagulant that ensures a steady, smooth flow of blood. Unfortunately, the mosquito’s saliva also may contain pathogens such as malaria parasites or encephalitis virus. This is how mosquitoes transmit disease.

Now chances are you won't sit there to try to identify what kind of mosquito is biting you so it will be gone before you realize you've been bitten or you will try to identify the smashed remains on whatever you used to kill it while it was biting you. But, just for your informaion, here is a list of the mosquitos and which ones pass what types of problems.

YELLOW FEVER MOSQUITO

YELLOW FEVER MOSQUITO

This is the mosquito that can spread the dengue fever, Chikungunya and yellow fever viruses, and other diseases. The mosquito can be recognized by white markings on legs and a marking in the form of a lyre on the thorax. The mosquito originated in Africa but is now found in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world.

Aedes aegypti is a vector for transmitting dengue and yellow fever. Understanding how the mosquito detects its host is a crucial step in the spread of the disease. Aedes aegypti are attracted to chemical compounds that are emitted by mammals which include us as humans. These compounds include ammonia, carbon dioxide, lactic acid, and octenol. Scientists at the Agricultural Research Service have studied the specific chemical structure of ocentol in order to better understand why this chemical attracts the mosquito to its host.

Although the lifespan of an adult Aedes aegypti is between two to four weeks depending on conditions, Aedes aegypti's eggs can be viable for over a year in a dry state, which allows the mosquito to re-emerge after a cold winter or dry spell. Dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) are acute febrile diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, which occur in the tropics, can be life-threatening, and are caused by four closely related virus serotypes of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. It was identified and named in 1779. It is also known as breakbone fever, since it can be extremely painful. Unlike malaria, dengue is just as prevalent in the urban districts of its range as in rural areas. Each serotype is sufficiently different that there is no cross-protection and epidemics caused by multiple serotypes (hyperendemicity) can occur. Dengue is transmitted to humans by the Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti or more rarely the Aedes albopictus mosquito. The mosquitoes that spread dengue usually bite at dusk and dawn but may bite at any time during the day, especially indoors, in shady areas, or when the weather is cloudy.

CULEX MOSQUITOES

CULEX MOSQUITOES

The West Nile virus is transmitted predominantly by Culex mosquitoes. Culex are medium-sized mosquitoes that are brown with whitish markings on the abdomen. These include the house mosquitoes (C. pipiens and C. quinquefasciatus) that develop in urban areas, and the western encephalitis mosquito (C. tarsalis) more commonly found in rural areas. They typically bite at dusk and after dark. By day they rest in and around structures and vegetation.

Culex lay “rafts” of eggs on still water in a variety of natural and man-made containers, including tree holes, ditches, sewage and septic system water, catch basins (storm drains), non-chlorinated swimming and wading pools, decorative ponds, bird baths, flower pots, buckets, clogged gutters, abandoned tires, and water-retaining junk and debris of all sorts. They cannot develop in running water and water that is present less than a week. Therefore, every effort should be made to prevent water from accumulating in containers or, at least, empty water out of them on a weekly basis.

Adult Culex mosquitoes do not fly far from where they develop as larvae. And unlike other mosquitoes that die with the coming of the first hard frost in autumn, the house mosquito can “over-winter” in protected places like sewers, crawlspaces and basements.

AEDES MOSQUITOES

The Aedes group of mosquitoes includes many nuisance mosquitoes, as well as species that transmit disease to humans. This is a diverse group that includes the inland floodwater mosquito (Aedes vexans), the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and the tree hole mosquito (Ochlerotatus triseriatus*) – all of which prefer to feed on the blood of mammals. Floodwater mosquitoes lay their eggs on soil that becomes flooded, allowing the eggs to hatch and larvae to develop in temporary pools. Asian tiger and tree hole mosquitoes are container-breeding mosquitoes, laying their eggs in small, water-filled cavities, including tree holes, stumps, logs, and artificial containers, such as discarded tires.

Inland floodwater mosquitoes are brown with pale B-shaped marks on their abdomens. They can become particularly bothersome after areas, such as river backwaters and other low lying places, become flooded.

Inland floodwater mosquitoes are brown with pale B-shaped marks on their abdomens. They can become particularly bothersome after areas, such as river backwaters and other low lying places, become flooded.

They are often the first mosquito noticed in spring, and later after heavy rainfall. Adults emerging together from flooded areas are often so numerous that natural controls, such as predators and parasites, are overwhelmed.

Unlike some other Aedes mosquitoes, inland floodwater mosquitoes may fly more than 10 miles from their larval development sites in search of blood meals. In Illinois, they may bite more people than any other species. They typically begin flying in late afternoon and are most active after dark, but will bite any time of day if disturbed while resting in shaded, heavily vegetated areas. Fortunately, in the United States they rarely, if ever, transmit disease, and typically die in autumn with the first hard frost.

Asian tiger mosquitoes are distinctive, black and white mosquitoes that bite by day (see picture on page 1). They were brought to this country in 1985, hidden in shipments of tires, and have since been found in many states including Illinois. The Asian tiger mosquito is capable of carrying LaCrosse encephalitis and West Nile viruses, though it is unclear whether the mosquito transmits these to humans.

The primary vector (carrier) of LaCrosse encephalitis is the tree hole mosquito. It is a dark mosquito with silvery white spots on the sides of its thorax and abdomen. Like the Asian tiger mosquito, the tree hole mosquito bites by day and lays its eggs in small containers where water will pool, such as tree holes, discarded tires, cans, buckets and barrels. They often are found in and around wooded areas.

* Ochlerotatus triseriatus, the tree hole mosquito, was formerly known as Aedes triseriatus.

MOSQUITO-BORNE ENCEPHALITIS DISEASES

MOSQUITO-BORNE ENCEPHALITIS DISEASES

The cycles of mosquito-borne viral encephalitis and meningitis diseases are similar. Most involve various bird species that are said to be reservoirs. Once infected by a mosquito bite, the reservoir species are usually not seriously affected. They will, at least for a time, produce enough virus in their bodies to infect mosquitoes. In this manner, mosquitoes pick up the virus and may become vectors, or organisms that transmit the disease to other animals, such as birds, horses or humans. Horses and humans are generally thought of as “dead-end” hosts because they do not produce enough virus to infect mosquitoes. Thus, dead-end hosts are not involved in the spread of disease.

For any particular season, the number of human encephalitis cases is not easily predicted. The occurrence of some encephalitides seems to be cyclic. This may be due to variations in the condition of infected birds in a reservoir population. Birds may harbor enough virus to facilitate transfer to mosquitoes that bite them for only a few days after being infected. After this, they do not serve as a reservoir for the virus. When more and more birds in an area have passed the infective stage, fewer birds are around to pass the virus to mosquitoes. Thus, fewer mosquitoes will carry the virus, and fewer people will be infected.

The variation in numbers of infective vs. non-infective birds in a population may play a big part in the cyclic nature of some viral encephalitis diseases. Of course, many other factors are involved, such as the availability of food and other resources influencing the size of bird populations; the availability of sites for the development of mosquito larvae, which influences the size of mosquito populations; as well as weather, including rainfall and temperature.

WEST NILE DISEASE

In recent years, the West Nile virus has been the most common disease vectored (transmitted) by insects and their relatives, including mosquitoes, other biting flies and ticks. West Nile virus arrived in the United States in 1999, inside an infected mosquito or bird. In 2002, Illinois led the nation in West Nile disease cases with 884 and 67 deaths.

Like all encephalitis producing viruses, West Nile virus survives in birds and/or mammals, using them as reservoirs. Most birds and mammals survive infection, while the mosquitoes that bite them can ingest the virus and infect other animals they bite, including humans. The virus can affect some birds and mammals, such as crows, blue jays, squirrels, horses and humans, more seriously than others, producing severe illness and death. However, about 80 percent of humans develop no symptoms after being infected with the virus, developing at least a temporary immunity. Persons older than 50 years of age, and those with compromised immune systems, are much more likely to develop West Nile fever, a flu-like disease that may last for weeks, or life-threatening nervous system complications such as meningitis or encephalitis.

ST. LOUIS ENCEPHALITIS

Similar to West Nile virus and also transmitted by Culex mosquitoes, the virus that causes St. Louis encephalitis is known for periodic outbreaks in the human population. In the United States, its occurrence has been limited compared to that of West Nile virus, and St. Louis encephalitis is usually confined to the southern portion of the United States, especially the Mississippi Valley. Compared to West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis has a lesser potential for producing epidemics. First noticed in St. Louis, Missouri, the largest epidemic occurred in the mid-70s when nearly 2,000 human cases were reported. Birds serve as a reservoir for the virus.

EASTERN and WESTERN EQUINE ENCEPHALITIDES

Outbreaks of these related encephalitis viruses are rare. Several different mosquito species are suspected vectors of Eastern equine encephalitis, while Culex tarsalis, known as the western encephalitis mosquito, is the vector of Western equine encephalitis. Their uncommon occurrence is fortunate because, of all encephalitides, the equine encephalitides may have the highest potential for human mortality.

CALIFORNIA ENCEPHALITIDES

This group of encephalitis viruses is unique in several ways -- it usually produces relatively mild illness in humans, and mammals, rather than birds, act as reservoirs for the virus.

The most common California encephalitis virus in the Midwest is LaCrosse. The LaCrosse virus is unique in that it primarily affects children, and because the virus can pass from a female mosquito to her offspring, mosquitoes can become infected without having to feed on an infected host.

Death from LaCrosse encephalitis is rare, but affected children may suffer from seizures and other nervous system complications that can persist for years. The disease is carried by Ochlerotatus triseriatus, the tree hole mosquito. It bites humans after feeding on squirrels and chipmunks. LaCrosse encephalitis is associated with wooded areas inhabited by these rodents. Because the tree hole mosquito develops in natural cavities and in artificial containers, and because adults do not fly far from their larval development sites, there is increased potential for LaCrosse encephalitis where tires and other debris accumulate near wooded areas.

PREVENTING MOSQUITO BITES

One strategy to prevent mosquito bites is avoidance. But even if one were to remain indoors throughout the mosquito season, they might still encounter mosquitoes. Mosquitoes, such as the house mosquito, are adept at getting into structures to feed on the inhabitants, and also to use crawlspaces, basements and cellars as quiet spots in which to shelter themselves for the winter. It is important to keep structures in good repair, maintaining the integrity of window and door screens and weather stripping, and screening or sealing all gaps through which mosquitoes might enter, such as spaces around utility lines, vents, foundation cracks, and gaps around windows and doors.

Repellents are the first line of defense against mosquito bites. Many products provide some degree of protection against mosquito bites. However, certain active ingredients provide better protection. For many years, DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) has been the standard by which products are measured. However DEET based products have proven deadly for the very young and old, so you have to consider that even though you may be healthy, your system is absorbing that poison causing unknown effects. Vitamin B1 and other organic repellents are as good if not better in my opinion.

If you have already been bitten and by some odd chance have some bananas around, peel the banana and put the inside of the peel over where you were bitten and in a brief period of time the itching will stop. If you want a DEET free repellent that is totally non-toxic, I have it!