|

The Maya and the Ka'kau' (Cacao)

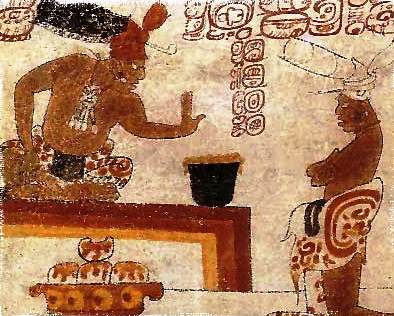

A lord tests the heat of his chocolate in this painting on a Late

Classic Maya vase from Pet�n;

note tamales (Maize cakes), covered with chocolate-chile sauce below

him.

"And so they were happy over the provisions of the good mountain,

filled with sweet things, . . . thick with pataxte and cacao. . . the

rich

foods filling up the citadel named Broken Place, Bitter Water Place".

Popol Vuh

Chocolate has a long and interesting history in Mesoamerica. From the

very beginning of Mesoamerican culture some 3500 years ago, it has been

associated with long distance trade and luxury. The

Pacific Coast of Guatemala, thought

to be the original source of Olmec culture, was, and remained, an

important area of cacao cultivation.

The Maya passed on the knowledge of cacao through oral histories,

stonework, pottery and the creation of intricate, multicolored documents

(codices) that extolled cacao and documented its use in everyday life

and rituals, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish. In the centuries

after initial contact between the Spaniards and indigenous peoples of

the New World, hundreds of descriptive accounts, monographs and

treatises were published that contained information on the agricultural,

botanical, economic, geographical, historical, medical and nutritional

aspects of cacao/chocolate.

The cacao tree called Madre Cacao, (Theobroma cacao "Food of the

Gods" a name coined by the swedish Linneus, that merged the greek

words "Theo" god "broma"

food with the Maya cacao) can be traced historically as well as archaeologically. Cacao,

native to the Americas, was used in both Mesoamerica and South America.

Cultivation, cultural elaboration and use of cacao were more extensive

in Mesoamerica, but it remains unclear which geographical location was

the center for domestication. The difficulty in identifying the wild

ancestors to modern cacao plays a role in this controversy. Although

some have argued for a South American center of domestication (Cheesman

1944, Stone 1984), other scholars have noted insufficient evidence to

support this thesis because the wild ancestors of cacao found in Central

America are genetically distinct from both current cultivars and South

American wild cacao plants. The South American subspecies T. cacao

spaerocarpum, has a fairly smooth melon-like fruit. In contrast, the

Mesoamerican cacao subspecies has ridged, elongated fruits. At some

unknown date, the subspecies T. cacao cacao reached the Pacific

lowlands of Mesoamerica and was later domesticated by the Maya and other

groups.

|

|

Glyph for Kakau in R�o

Azul Pot (460 AD)

|

The

word cacao originated from the Maya word

Ka'kau', and, as well as the chocolate Maya

word Chocol'haa and the verb

chokola'j "to drink chocolate together",

were then adapted centuries later by the aztecs. The Maya

believed that the ka'kau' was discovered by the gods in a mountain

that also contained other delectable foods to be used by the Maya.

According to Maya mythology, Hunahp�

gave cacao to the Maya after humans were created from maize by the divine

grandmother goddess Ixmucan�. (Bogin 1997, Coe 1996, Montejo 1999, Tedlock

1985). The Maya celebrated an annual festival in April to honor their

cacao god, Ek Chuah (left), an event that

included the sacrifice of a dog with cacao colored markings; additional

animal sacrifices; offerings of cacao, feathers and incense; and an

exchange of gifts. Michael Coe, Professor of

Anthropology, and curator emeritus in the Peabody Museum at Yale, and

coauthor of the book "The True History of Chocolate" (1996),

states that the word chocolatl appears in "no truly early source on the

Nahuatl language or on Aztec culture. Furthermore, He cites the distinguished

Mexican philologist Ignacio Davila Garibi, who proposed the idea that the

"Spaniards had coined the word by taking the Maya word chocol and then

replacing the Maya term for water, haa, with the Aztec one, atl." The

word cacao originated from the Maya word

Ka'kau', and, as well as the chocolate Maya

word Chocol'haa and the verb

chokola'j "to drink chocolate together",

were then adapted centuries later by the aztecs. The Maya

believed that the ka'kau' was discovered by the gods in a mountain

that also contained other delectable foods to be used by the Maya.

According to Maya mythology, Hunahp�

gave cacao to the Maya after humans were created from maize by the divine

grandmother goddess Ixmucan�. (Bogin 1997, Coe 1996, Montejo 1999, Tedlock

1985). The Maya celebrated an annual festival in April to honor their

cacao god, Ek Chuah (left), an event that

included the sacrifice of a dog with cacao colored markings; additional

animal sacrifices; offerings of cacao, feathers and incense; and an

exchange of gifts. Michael Coe, Professor of

Anthropology, and curator emeritus in the Peabody Museum at Yale, and

coauthor of the book "The True History of Chocolate" (1996),

states that the word chocolatl appears in "no truly early source on the

Nahuatl language or on Aztec culture. Furthermore, He cites the distinguished

Mexican philologist Ignacio Davila Garibi, who proposed the idea that the

"Spaniards had coined the word by taking the Maya word chocol and then

replacing the Maya term for water, haa, with the Aztec one, atl."

There are several mixtures of cacao described in ancient texts, for

ceremonial and medicinal uses, as well as culinary purposes. Some mixtures

included maize, chili, vanilla (Vanilla planifolia), peanut butter and

honey. Chocolate was also mixed with a variety of flowers, and sometimes

it was thickened with atol, a corn gruel. There were numerous

variations, including a red variety made by adding annatto dye

(achiote). Archaeological evidence for use of cacao, while relatively

sparse, has come from the recovery of whole cacao beans at

Uaxact�n, Guatemala (Kidder 1947) and from

the preservation of wood fragments of the cacao tree at

Chocol� and Takalik Abaj,

in the pacific lowlands. In addition, analysis of residues from the

interiors of four ceramic vessels from an Early Classic period (ca. AD

460-480) tomb at R�o Azul in northeastern

Guatemala has revealed the presence of theobromine and caffeine. As

cacao is the only known source from Mesoamerica containing both of these

compounds, it seems likely that these vessels were used as containers

for cacao drinks. In addition, cacao is named in a hieroglyphic text on

one of the vessels, a stirrup-handled pot with an intricately locking

lid. The Maya drank its Chocolate hot and frothy that was produced by pouring

the drink back-and-forth from a height or with a beater (molinillo).

One of the earliest images of this froth-producing process is the Maya

Princeton Vase from the Late

Classic. It was very useful in the

Maya Medicine too, both as a primary

remedy and as a vehicle to deliver other herbal medicines.

|

|

|

Princeton Vase (Pet�n Lowlands). |

|

Vase from Nebaj, Quich�,

Guatemala Highlands, depicting a cacao tree.

|

Christopher Columbus was the first European to come in contact with

cacao. On August 15, 1502, on his fourth and last voyage to the

Americas, Columbus and his crew encountered a large dugout canoe near

the Guanaj� island off the coast of what is now Honduras. The canoe was

the largest native vessel the Spaniards had seen. It was "as long as

a galley," and was filled with local goods for trade, including cacao

beans. Columbus had his crew seize the vessel and its goods, and

retained its skipper as his guide.

Later, Columbus' son Ferdinand wrote about the encounter. He was struck

by how much value the Native Americans placed on cacao beans, saying:

"They seemed to hold these almonds (referring to the cacao beans) at a

great price; for when they were brought on board the ship together with

their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all

stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen."

|

|

|

R�o Azul "Chocolate" pot.

|

Chocolate was made from roasted cocoa beans, water and a little spice:

and it was the most important use of cocoa beans, although they were

also valued as a currency. An early explorer visiting Guatemala found that:

A large tomato was worth one bean, a turkey egg was 3 beans, 4 cocoa beans could buy a pumpkin, 100 could buy a rabbit

or good turkey hen, and 1000

a slave. Cacao beans were worth transporting for long distances because

they were luxury items. In Maya times, one of the privilege of the elite

(the royal house, nobles, shamans, artist, merchants, and warriors) was

to drink chocolate.

Maya Merchants often traded cocoa beans for other commodities,

and for cloth, Jade and ceremonial feathers. Maya farmers transported

their cocoa beans to market by canoe or in large baskets strapped to

their backs, and a Mecapal, (forehead band

tied to the basquet). Wealthy merchants traveled further, employing porters, as

there were no horses, pack animals or wheeled carts in Central America

at that time. Some ventured as far as Teotihuacan, introducing them to

the much-prized cocoa beans, it was also traded with the Tainos from

Cuba and the Quechua from South America.

Mesoamerican Commerce Routes and goods production, from the Pre

Classic to the Post Classic

The Spaniards didn't like it at the beginning, as we can see in this

description form the friar Jos� de Acosta in Per�: "Loathsome to such as

are not acquainted with it, having a scum or froth that is very

unpleasant to taste. Yet it is a drink very much esteemed among the

Indians, where with they feast noble men who pass through their country.

The Spaniards, both men and women, that are accustomed to the country,

are very greedy of this Chocolat�. They say they make diverse sorts of

it, some hot, some cold, and some temperate, and put therein much of

that 'chili'; yea, they make paste thereof, the which they say is good

for the stomach and against the catarrh."

Although soon the chocolate would make its way across the

Atlantic, first to Spain, and then to the rest of Europe. Chocolate,

prepared as a beverage, was introduced to the Spanish court in 1544 by

Kek'ch� Maya nobles, brought from Cob�n,

Guatemala, by Dominican friars to meet Prince Philip. The first

load of beans arrived to Sevilla, Spain in 1585. (Coe and Coe

1996). Within a century, the culinary and medical uses of chocolate

spread to France, England and elsewhere in Western Europe. Demand for

this beverage led the French to establish cacao plantations in the

Caribbean, while Spain subsequently developed their cacao plantations in

their Philippine colony (Bloom 1998, Coe and Coe 1996, Knapp 1930).

Cacao subsequently flourished in the 1880s after introduction as a

commercial crop to the English Gold Coast colonies in West Africa.

For the Chocolate connoisseur, here's an article published by someone who helped me on some details on this page. lick here

|